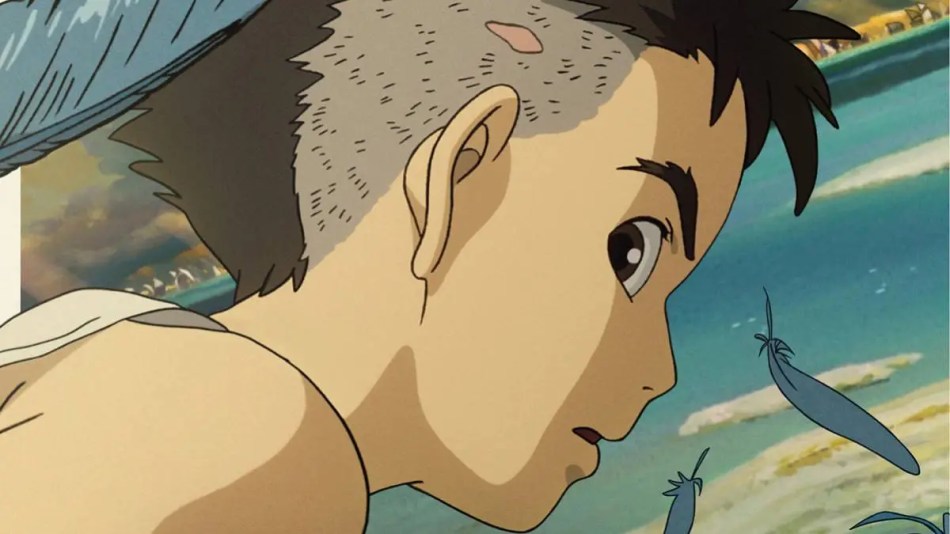

Set during the Pacific War, teenage Mahito (Soma Santoki) sees his life abruptly upended by the horrors of warfare. When his home city of Tokyo is bombed, his mother dies in a hospital engulfed by flames. In the aftermath of this loss, his father Shoichi (Takuya Kimura), a munitions factory owner, takes Mahito to safety and marries his late wife’s younger sister, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura). In their new home, an intrusive heron begins to linger ominously around the family home, and Mahito also discovers a mysterious, abandoned tower in the nearby forest. The encounters with the heron grow increasingly provocative, leading Mahito and housemaid Kiriko (Ko Shibasaki) into the secluded confines of the tower.

Set during the Pacific War, teenage Mahito (Soma Santoki) sees his life abruptly upended by the horrors of warfare. When his home city of Tokyo is bombed, his mother dies in a hospital engulfed by flames. In the aftermath of this loss, his father Shoichi (Takuya Kimura), a munitions factory owner, takes Mahito to safety and marries his late wife’s younger sister, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura). In their new home, an intrusive heron begins to linger ominously around the family home, and Mahito also discovers a mysterious, abandoned tower in the nearby forest. The encounters with the heron grow increasingly provocative, leading Mahito and housemaid Kiriko (Ko Shibasaki) into the secluded confines of the tower.

Miyazaki has not simply created a ‘greatest hits’ compilation of prior works here. Alice in Wonderland, The Labyrinth, and The Wizard of Oz could be cited as influences, but it is the more autobiographical elements of The Boy and the Heron that really hit home. Narratively, Miyazaki is ambitious as he jumps from moment to moment, idea to idea, and it is through his storytelling style that many of these ideas gradually form a larger thematic picture.

Drawing upon the various influences and his unique narrative style, Miyazaki crafts a multitude of visuals that serve to mirror and deepen the story’s expansive themes. There are many images within the film that are reflective of its broader plot. The abandoned tower, for example, is somewhat reminiscent of the magical world of Spirited Away or Howl’s Moving Castle. Mahito’s new home, which merges traditional Japanese architecture with Western elements, reflects a transition from the ‘old world’ into something ‘new’. The film is a feat of visual storytelling. It is littered with striking landscapes, odd dimensions, absurd animals, and powerful character interactions. The projection of the real world and its tragedies are explored on a grand scale through deeply spiritual and surreal shifts. The heron, for example, at first a majestic bird soaring through picturesque landscapes, soon reveals itself as a disguise for a bulbous little man (Masaki Suda). It is both funny and unsettling as this odd character appears inside the bird’s body, which is perhaps a metaphor for Mahito’s loneliness in his new environment.

Anchored in the poignant journeys of its characters, the film delves into the existential question of how we choose to live our lives. Through the connection between Mahito and a character we meet within the fantasy world, Himi (Aimyon), the film’s statements on loss, specifically of a parent, become central. It is within their shared dreamlike world that both Mahito and Himi begin to confront their grief. Both make the decision to leave this fantasy world within the tower in favor of confronting the harsh truths of existence – conflict, suffering, and loss. Himi, in particular, aware of her choice, despite recognizing it will pave the way to her downfall, underscores the film’s heartfelt message: It’s not our departure, but how we live that matters. In many ways, this narrative thread encapsulates Miyazaki’s storied legacy of blending the fantastical with raw human emotions. It is a testament to his ability to navigate the complexities of the human experience through enchanting and surreal realities.

Discover more from Cineccentric

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

0 comments on “The Boy and the Heron ★★★★”