Suffocating. Pablo Larraín‘s trilogy on important 20th century women can be best described by that feeling. Jackie finds Jacqueline Kennedy (Natalie Portman) engulfed by tradition, grief, and mythos, all while she struggles to catch her breath in the wake of John F. Kennedy’s (Caspar Phillipson) assassination. Spencer finds Princess Diana (Kristen Stewart) constricted by structure and obligation, while very literally feeling constrained by a pearl necklace and boxed in at Christmas festivities. Maria follows opera singer Maria Callas (Angelina Jolie) in her final week of life. Her voice may be beautiful, but in this final week, she struggles to have the words come out with her gift for music turning on her. It is straining her fragile body, while she, like Jackie and Diana, struggles with the prying eyes of a world that expects everything. In a flashback, she attends the birthday party of John F. Kennedy (Phillipson reprising his role) with her then-partner Aristotle Onassis (Haluk Bilginer). Maria tells Kennedy that, “You and I belong to a very, very small group of lucky angels who can go anywhere we want in this world. But, we can never, ever get away.”

Larraín’s haunting biopics that eschew detail in favor of feeling and emotion have all, in my opinion, been excellent and Maria is no exception. It never shies away from demonstrating her “diva” tendencies, even having her directly confronted for her past bad behavior of cancelling shows for faked illnesses or her demanding nature with her loyal staff, Ferruccio (Pierfrancesco Favino) and Bruna (Alba Rohrwacher). She is not all good, but she is human and as Larraín demonstrates, remarkable. She is a once-in-a-lifetime performer, a singer who truly inhabits every feeling of her characters while bringing the songs to life to their fullest potential. Real recordings of Maria Callas fill Maria in colorful, show-stopping performances that capture what would draw Larraín to this subject. But, as much as the film celebrates her, it presents her life as though it were an operatic tragedy. Her voice is mostly gone, shown largely in those flashbacks, and she recounts details of her life to a journalist making a film about her, Mandrax (Kodi Smit-McPhee) – Larraín used a similar framing device in Jackie with a journalist (Billy Crudup), though in this film, Mandrax is a hallucination (and named after a drug Maria is addicted to), a self-reflexive surrogate for Larraín and representation of Maria’s fragile mental state – while trying to live life for herself again in 1977 Paris. Having lived through a turbulent romance with Aristotle Onassis and having largely performed in her life for an audience that demanded it of her, she strives to sing now for herself and finds that music eluding her. All the while, her doctor warns that the strain could kill her with her liver and heart in various stages of failure.

Nothing can be private or just for her. She has live-in help that love her but place demands upon her she does not want (namely when it comes to avoiding her health issues), while even in her mind, the press picks apart her every decision in life and then, in reality, the press upstages one of her “rehearsals” to accost her about what she is preparing for and to alert her to how bad she sounds now. As with Jackie and Spencer, she is a woman who is solely defined by what others think and has lived a life in the shadow of that expectation. The true Maria is hardly even known to her, having so long taken a backseat to put the side of herself known as “La Callas” into the spotlight. Maria’s self-reflexivity calls attention to its artificiality, while creating a stage for Maria to perform upon once again. He is not after defining her or in fulfilling the traditional biopic expectations. Rather, he is after re-creating her essence and allowing the audience to spend two hours with this woman with a voice larger than life.

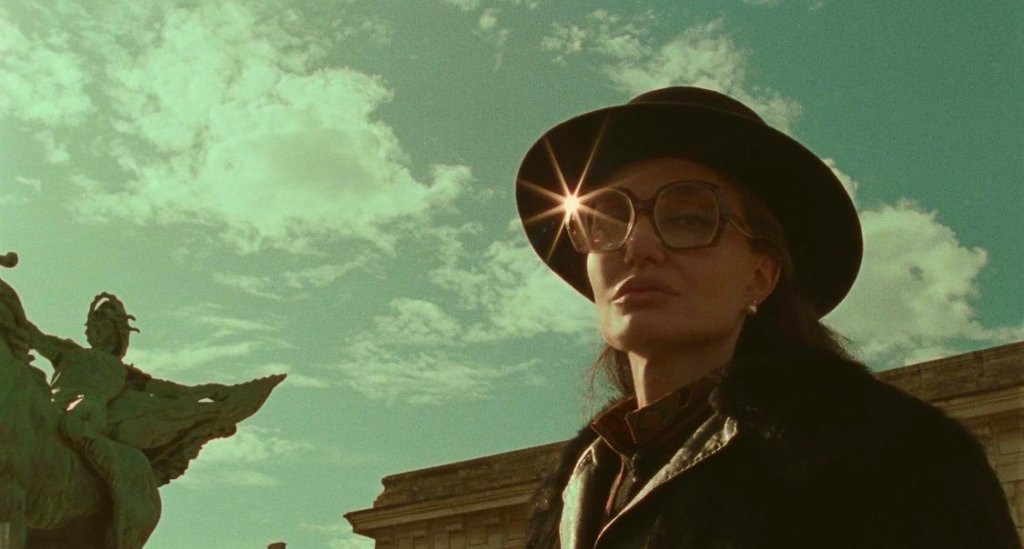

Angelina Jolie is essential to this, giving one of the best performances of her career. She is a revelation. There is a grace and an elegance to her take on Maria. She seems to float on the air, striding about Paris and hiding behind her large framed glasses. Jolie largely lip syncs actual Maria Callas performances, but her embodiment of Callas is absolute. She perfectly captures her essence and aura, standing before an audience with a fire and passion within her that seems to, as she claims, rise “from her belly and out of her mouth.” Even in the present, where her voice struggles to reach its past heights, Jolie’s embodiment of how these imperfections harm her and the struggles that Maria faces to elicit this voice from within her again, is impeccable. She knows the notes and how she could once perform it, while she feels every bit of the gulf between what was and what is now. It is this suffocating strain to be herself again, a fight against the gift she has that has turned into a curse that creates so much of Maria’s anguish, a feeling Jolie exemplifies with great depth and feeling. Jolie heightens and truly disappears into being Maria Callas, inhabiting her every suppressed feeling. Flashback scenes of her performing or of her mingling with the upper-crust capture her headstrong, individualistic, and fiery personality, all of which still exist in the present but with a new self-doubt and uncertainty. She is still as sharp-tongued as ever, but the little bits of wavering and tepidness help to make this diva into a transfixing and achingly human figure.

Further crucial to Maria’s success is the work of DP Edward Lachman, editor Sofía Subercaseaux, and production designer Guy Hendrix Dyas. From its early frames, Maria is utterly transfixing. Dyas’ note-perfect and highly detailed sets are wonderfully shot by Lachman with a few symmetrical shots with deep focus capturing every inch of splendor in the film’s interiors. Lachman’s camera is especially striking as it moves about, notably in tracking shots – Spencer, too, heavily used tracking shots to great effect – where the camera calls attention to itself in its often floating, rapid movements. A tracking shot through a park that rapidly catches up to Maria, then twists into a profile shot of her upright and proud stride, is stunning, a shot that feels like a musical crescendo that builds into a grand pay-off of Jolie’s expressive face. The film’s hyperreal style blends into the hallucination scenes, especially one influenced by Madame Butterfly. The striking red-colored performers form a circle, contrasted by green and gold exteriors and performers in the background, while the camera pulls into the edge of the circle, seeming to float through the crowd, and then landing on Jolie in the middle with her face enraptured by her performance and the music in her head. Lachman, in an interview with Variety, noted that the film aimed to create a “heightened reality” and his work exemplifies this with the camera turning into a crucial tool for the film.

Maria is a tragic and stirring look at Maria Callas. Angelina Jolie turns in the performance of her career, while director Pablo Larraín closes his trilogy on important 20th century women with another brilliantly expressive and deeply felt film. It is not a trilogy about the details, but rather one about bringing the viewer into the minds of these women and enabling us to see the world from their eyes. In this, it brings to the forefront that shared feeling that the walls are closing in, and their lives are more prisons than avenues for them to express their true selves. It may be luxurious and she may be more familiar with the spotlight, but it is suffocating.

Discover more from Cineccentric

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

0 comments on “Maria ★★★★”